Third Quarter, 2025

Click here for a printable version of the Investment Update.

Listen to our latest Investment Update on Apple Podcasts, Pandora or Spotify.

As capital markets extend a remarkable but volatile streak of strong performance, we explore the headwinds and tailwinds being navigated by U.S. companies and explain how we are adjusting portfolios to find opportunity amid rapid change. We also share our perspective on recent developments in private equity.

A QUARTER OF STRONG RETURNS BUT GROWING UNCERTAINTY

The U.S. equity markets continued to defy gravity in the third quarter of 2025. The S&P 500 delivered a total return of 8.1% in the quarter, bringing its year-to-date return to 14.8%. Non-U.S. equity markets were also strong, with the MSCI EAFE Index1 generating a total return of 4.9% in the third quarter and an impressive 25.8% year to date. During the third quarter, U.S. equities were buoyed by:

- Solid second-quarter earnings results, which exceeded lowered expectations

- The prospect of interest rate cuts, the first of which took place in September

- Easier financial conditions, due to higher stock prices and a continued slide in the U.S. dollar, which contributed to the earnings growth noted above

- Optimism about tax cuts and fiscal stimulus resulting from the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (“OBBBA”)

- Continued torrential corporate spending on Artificial Intelligence (“AI”) infrastructure around the country

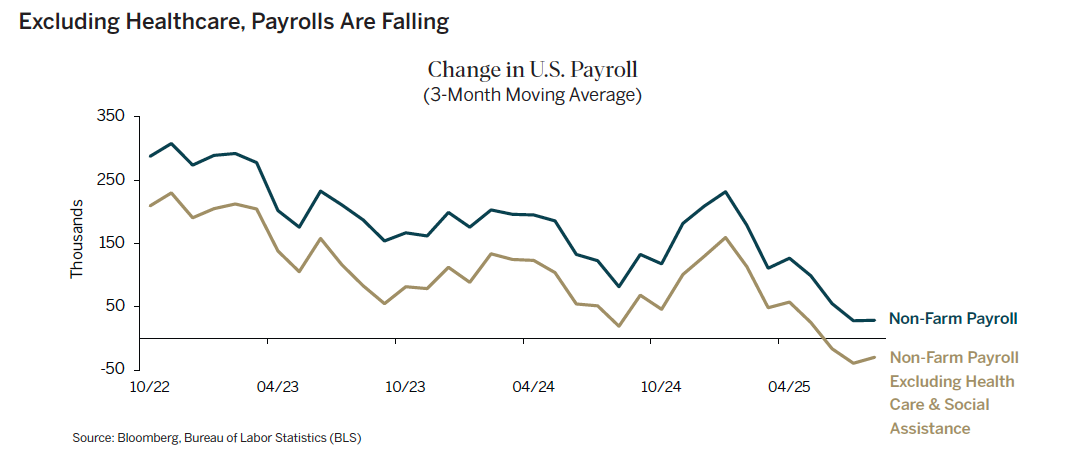

The Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model projects U.S. Gross Domestic Product (“GDP”) growth was a strong 3.8% in the third quarter. Nonetheless, employment growth has decelerated sharply. Excluding the less economically sensitive health care sector, the three-month moving average in private payrolls fell by 30,000 in August.

How can we reconcile this unusual discrepancy between solid U.S. GDP growth and weak employment? By definition, GDP growth equals employment growth times productivity growth. Therefore one of three scenarios must unfold:

- A long-awaited productivity boom could develop. AI or increased digital investment made during the pandemic could be contributing to economic growth without employment growth. This would be the best outcome for U.S. equities, because if continued, it could usher in a sustained disinflationary boom. However, surveys of companies using AI do not show this to be the case yet. A recent McKinsey poll found that, while almost 80% of companies are now using generative AI, the vast majority have not seen a bottom line benefit from it. Another study by researchers at MIT found that 95% of companies have seen no gains from their AI investments.

- Employment growth could catch up to GDP growth. This scenario would have mixed implications for stocks. On the one hand, concerns about rising unemployment would fade. On the other hand, stronger demand for labor could push up wages, fueling inflation, which has remained stubbornly above the Fed’s 2% target. Higher inflation could, in turn, keep the Fed from cutting rates as much as the market currently expects, disappointing investors.

- Employment growth could remain low and economic growth could slow. Falling or flat demand for labor, coupled with nearly 3% inflation, would cause real income growth to be weak. With pandemic savings largely depleted, consumer loan delinquency rates up and home prices no longer rising, slow income growth could cause consumer spending to stumble, tipping the economy into recession. This would be the worst-case scenario for stocks. Given the widespread ownership of equities in the U.S., even a relatively small decline in equity prices could lead to a meaningful pullback in spending, thereby creating a negative feedback loop, in which lower equity prices lead to lower consumption, which then causes equity prices to fall further.

High valuations and widespread investor optimism lead us to believe that most people are betting on Scenario 1. We think the odds are greater that either Scenario 2 or 3 unfolds.

CAN U.S. CORPORATE EXCEPTIONALISM CONTINUE?

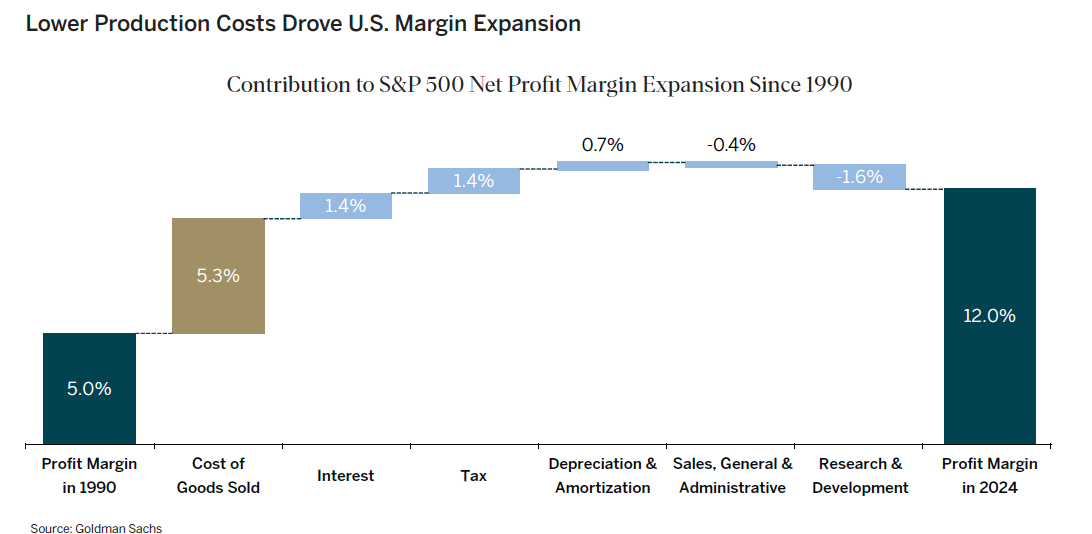

While the U.S. economy has grown faster than other high-income economies in recent decades, U.S. companies have increased their profitability even faster than economic growth alone would suggest. The magnitude of U.S. earnings growth has been integral to the record 25 years of U.S. equity market outperformance.

For global investors, determining whether U.S. outperformance can continue is of paramount importance, especially now, when U.S. policy changes may reduce some tailwinds that helped U.S. companies achieve these spectacular results.

Since 1990, several factors drove the exceptional margin expansion of U.S. companies.

OUR INVESTMENT THEMES

Ironically, just when the U.S. appears to be taking a less laissez-faire approach to industrial policy, many other countries are moving in the opposite direction. Many of the policies outlined in Mario Draghi’s recent report on European Union competitiveness are explicitly designed to improve European profit margins by reducing barriers to intra-European trade and by lowering input and borrowing costs.IN CONCLUSION

We find ourselves at a moment of unprecedented change and uncertainty, where there are a broad range of possible economic and market outcomes. The industrial policies of the U.S. and many other economies are becoming more mercantilist. Corporate investment in AI remains unabated despite limited commercial benefits thus far. We are navigating this moment with discipline, adjusting portfolios as opportunities emerge. We are also making sure to adhere to and continuously refine our time-tested approach to Thematic research and investing, which we believe will continue to serve clients well.

(1) The MSCI EAFE Index is an equity index that captures large and mid-cap representation across 21 developed markets countries (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK). The Index excludes the US and Canada.

BEWARE GREEKS BEARING GIFTS: THE “DEMOCRATIZATION” OF PRIVATE EQUITY

Private Equity (“PE”) funds have long been portrayed as the Rolls Royces of the investment world. With typical minimum investments of $5 million or more, PE has been the exclusive preserve of ultra-wealthy families and the largest institutions. And rightly so. Few investors have the financial wherewithal and long investment horizon needed to accept the lack of liquidity, transparency and decision rights in this asset class.

But now, some of the biggest names in PE are throwing open their doors to anyone who can make a minimum investment of $25,000 in a new class of retail-oriented funds, an effort trumpeted as “democratizing” PE.

One can’t help thinking of the Greek army’s gift of a large wooden horse to the city of Troy in The Aeneid. PE managers aren’t welcoming the public into this asset class to be kind. They created these new retail funds in response to poor recent investment performance, lengthening periods of illiquidity and challenging fund manager economics.

DISAPPOINTING PERFORMANCE

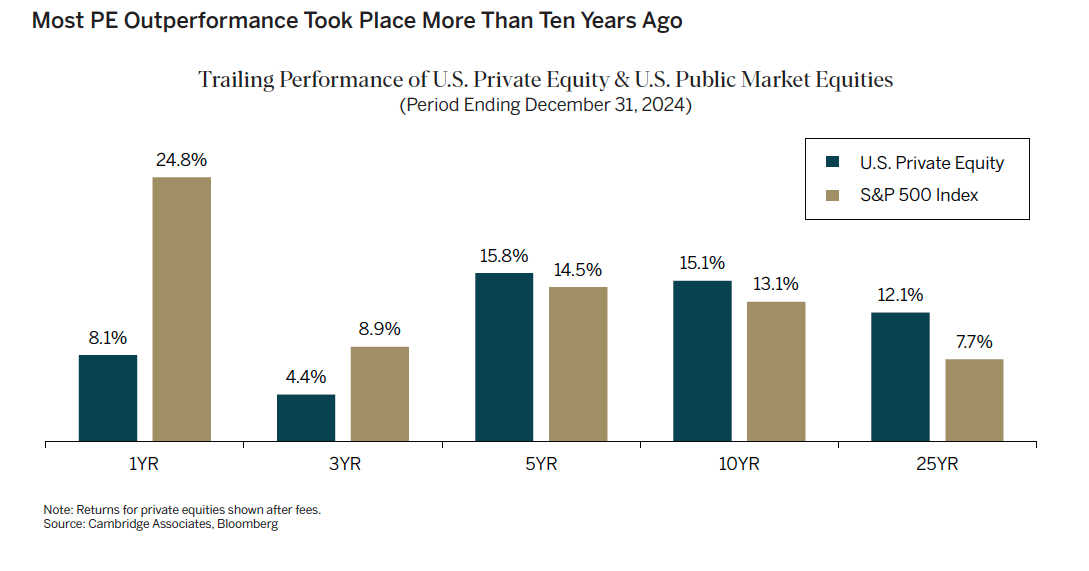

Long-time investors are dissatisfied with recent PE returns and increasingly concerned that future returns may be no better. As of the end of 2024, PE as a category had underperformed the S&P 500 after fees over the one- and three-year periods and delivered returns close to public equity indices over the five- and ten-year periods. While PE did materially beat the S&P 500 over a 25-year period, most of that outperformance occurred in the early part of that long time span.

What went wrong? As is often the case on Wall Street, early success led to too much money chasing too few opportunities. PE emerged as a small but prominent asset class in the 1980s. Functioning basically as leveraged value investors, PE funds used debt to buy controlling interests in companies at low prices, with the goal of selling them at much higher prices after improving operations or breaking them up to capture the value of their parts.

Despite some spectacular failures – most notably KKR’s $25 billion buyout of RJR Nabisco in 1989, which lost roughly $730 million over 15 years – many early PE investments generated hefty returns. The success of early adopters, such as the Yale University endowment, attracted other institutional investors, leading to an explosion in PE assets under management. PE grew from roughly $600 billion in 2000 to almost $10 trillion in 2024, with another $2 trillion in contractually committed capital.

PE is no longer a niche, nimble asset class, and it becomes much harder to earn a high return on investment after the amount of capital to invest increases more than 15-fold.

To deploy ever greater pools of capital, PE firms have been forced to do bigger deals. In 2009, only 4% of PE deals in North America were valued at greater than $1 billion. In 2024, $1 billion-plus deals accounted for 22% of transactions.

The pressure to invest has also driven up valuations at purchase. In 2009, PE firms were buying companies at average multiples that were 40% below multiples for comparable public equities. That discount has narrowed over the past three years to less than 5%.

In late September, a consortium led by Silver Lake and Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund announced the $55 billion purchase of Electronic Arts (“EA”), a video game maker, setting a record for the largest PE transaction ever. The purchase price represents a 25% premium to EA’s closing share price on NASDAQ the day before deal talks were reported by The Wall Street Journal.

Complicating matters further, the increased cost of debt to fund purchases is not just an additional drag on investment returns. Higher debt levels increase the risk of portfolio company bankruptcy at times of economic stress.

LIQUIDITY PRESSURES

Institutional investors in PE are facing a liquidity crunch due to a three-year-long drought in distributions. With the decline in M&A activity and initial public offerings in recent years, PE funds have struggled to exit investments. On average, they are holding investments longer. These longer holding periods both lower annualized returns and delay distributions to investors.

For endowments, the liquidity strain is particularly difficult to tolerate. Many universities and other entities now face uncertain government funding, increased tax exposure and challenging enrollment and tuition trends. As a result, many are now selling some of their private equity stakes at a discount in the secondary market to gain liquidity. Secondary market activity has nearly tripled in value over the past four years.

MANAGERS NEED ASSET GROWTH

Traditional PE fundraising has declined in each of the past three years, limiting the growth in assets under management. Without ample new capital, PE funds may not have the revenue growth needed to support current investments and attract, retain and compensate the investment professionals and operating partners they need to identify new investment targets and create value in portfolio companies.

NOW ENTER “DEMOCRATIZATION”

That’s where “democratization” and the new retail funds come in. Wall Street is looking for a new revenue stream, using the elite reputations of PE managers to sell PE retail funds to the masses. PE managers, in turn, are seeking to grow assets under management, revenues and profits. And legacy PE investors are hoping to gain the liquidity they need by selling old investments to these new retail funds.

While we believe that many PE investors stand to make money in the coming decades, outsized returns are likely to be far harder to come by than in the early days of the asset class. Only those clients that can handle prolonged periods of illiquidity and tolerate the category’s opacity and lack of control should delve into PE investing. And perhaps more than ever, careful manager and vehicle selection will be key to avoiding the modern financial equivalent of a Trojan Horse.

Important Disclosures This commentary is for informational purposes only. The information set forth herein is of a general nature and does not address the circumstances of any particular individual or entity. You should not construe any information herein as legal, tax, investment, financial or other advice. Nothing contained herein constitutes a solicitation, recommendation, endorsement, or offer to buy or sell any securities or other financial instruments. This commentary includes forward-looking statements, and actual results could differ materially from the views expressed. Materials referenced that were published by outside sources are included for informational purposes only. These sources contain facts and statistics quoted that appear to be reliable, but they may be incomplete or condensed and we do not guarantee their accuracy. Fact and circumstances may be materially different between the time of publication and the present time. Clients with different investment objectives, allocation targets, tax considerations, brokers, account sizes, historical basis in the applicable securities or other considerations will typically be subject to differing investment allocation decisions, including the timing of purchases and sales of specific securities, all of which cause clients to achieve different investment returns. Past performance is not indicative of future results, and there can be no assurance that the future performance of any specific investment or investment strategy will be profitable, equal any historical performance level(s), be suitable for the portfolio or individual situation of any particular client, or otherwise prove successful. Investing involves risks, including the risk of loss of principal. The level of risk in a client’s portfolio will correspond to the risks of the underlying securities or other assets, which may decrease, sometimes rapidly or unpredictably, due to real or perceived adverse economic, political, or regulatory conditions, recessions, inflation, changes in interest or currency rates, lack of liquidity in the bond markets, the spread of infectious illness or other public health issues, armed conflict, trade disputes, sanctions or other government actions, or other general market conditions or factors. Actively managed portfolios are subject to management risk, which involves the chance that security selection or focus on securities in a particular style, market sector or group of companies will cause a portfolio to incur losses or underperform relative to benchmarks or other portfolios with similar investment objectives. Foreign investing involves special risks, including the potential for greater volatility and political, economic and currency risks. Please refer to Chevy Chase Trust’s Form ADV Part 2 Brochure, a copy of which is available upon request, for a more detailed description of the risks associated with Chevy Chase Trust’s investment strategy. The recipient assumes sole responsibility of evaluating the merits and risks associated with the use of any information herein before making any decisions based on such information.